Cecelia McCall, retired Baruch College English Department, former PSC Secretary and Legislative Director

Let me thank the Governing Board for the opportunity to speak, and I want to congratulate you on all of the work. I’d also like to congratulate the Kingsborough people for that wonderful presentation on the election. It’s the kind of election we ran twenty years ago.

There’s not a lot on paper about the New Caucus, so what you’re going to hear are basically my reflections on it and how I see it. For most of my tenure at CUNY I was not involved with the union. That there was a union chapter at Baruch was a closely guarded secret, and so my activism for many years was through the University Faculty Senate. When I was elected Secretary in 2000, I was then the Vice-Chair of the University Faculty Senate, slated to become the next chair; however, I opted for the union. I’ll speak for a few minutes about the context within which the New Caucus was born, and John will address more directly the development and the nitty gritty of the New Caucus. If time permits, we’ll both mention our experience after wresting the PSC from CUC, and perhaps Barbara will join us, for no one was more surprised than the four of us when we won.

The official record of the New Caucus states that it began as an insurgent caucus within the PSC in 1995. But I would like to contend that it began long before then. Perhaps twenty or 25 years earlier, during the struggle to maintain free tuition and open admissions. And I have to say as well that I can’t imagine the New Caucus without the particular individuals involved in that effort. As I reflect – these are my reflections, I have to warn you – I see two primary groups: activist Jews and lapsed Catholics. Some of you may want to contend that, but as I said these are my reflections. The former were largely native New Yorkers who grew up in socially conscious working-class families at a time when New York was a blue-collar labor town that provided a host of public services, such as municipal hospitals, community clinics, sports and afterschool programs. They were joined by people like Dave Kotelchuk and Steve Leberstein, not natives but with similar backgrounds and a commitment to social justice. And there were people like me, lapsed Catholic; John can speak for himself. I grew up elsewhere, in a working-class family that was neither racially nor socially conscious, denying its heritage and hiding out in the Jewish ghetto passing for white. When I moved here in the mid-Sixties, I became immersed in the struggle for community control and was first arrested in a demonstration for jobs in construction for African Americans at the Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn. I knew nothing about CUNY and was teaching at NYU at the developmental skills clinic when I read an article in the Times about the SEEK program and its mission to provide developmental assistance to Black and Puerto Rican students. I said, That’s for me.

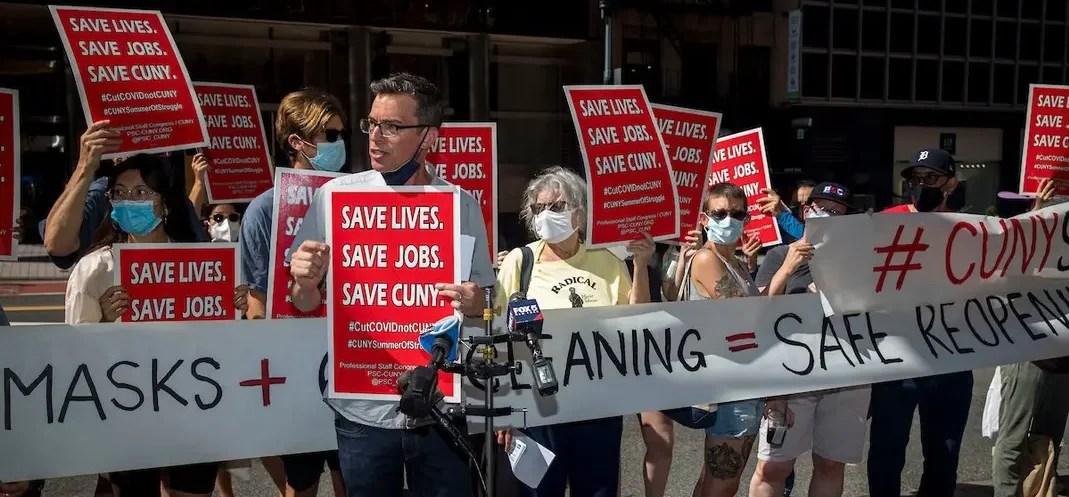

I and other colleagues were on the line at City College when Black and Puerto Rican students closed the campus, demanding the expansion of SEEK and College Discovery, and the acceleration of the Board of Education’s plan to provide a place at CUNY for any student graduating from the New York City public high schools. And we were on the line again when CUNY trustees voted in 1998 at the insistence of then-mayor Giuliani to end remediation at the senior colleges and thus end open admissions. I just want to show you this photograph that was in the New York Times and was given to me as a gift when I retired from the union. So you know who the grey-haired lady there, with her hands cuffed behind her, but do you know who that guy is with his hands handcuffed as well, committing c.d.? Mike Fabricant. Mike and I didn’t know each other. We were from different campuses but were among the concerned faculty who had been involved in the ongoing fight to keep the university accessible from the moment tuition was imposed and the state assumed responsibility for funding the senior colleges. We understood that CUNY was the locus of a class struggle, contested territory, an example of what a free, quality, public higher education could be. While to the ruling class, CUNY was a symbol of all they considered wrong with New York: a city too generous to working class people. CUNY was attacked by politicians and policy makers in Washington DC, Albany, and the city because it was free, without tuition, and enrolling students of color. The fiscal crisis of the Seventies was the pretext to shift public resources from the working class to the business class. It was the kind of shock to the system described by Naomi Klein that enabled neo-liberalism to gain a foothold and transform New York into two cities: one of the very rich, and the other all the rest of us. It was the beginning of the transfer of the resources of social services and communities to the elite in the form of tax abatements, tax cuts, and tax credits, the beginning of austerity budgets at CUNY that we have yet to escape from, and the beginning of the corporatization of the university.

Austerity budgets at CUNY have meant too few full-time faculty, too few counselors, and too many overtaxed adjuncts, the closing of departments, and the burgeoning of class size. Throughout the years, we formed various faculty committees and organizations, such as Concerned Faculty at CUNY, to contest the corporatization and the sundry testing schemes that did nothing but shrink the enrollment of students of color at the senior colleges, and the state’s never living up to its funding obligation, even suing the Governor and the Comptroller. We were scattered across the campuses and never realized mass organization. That, we felt, was the union’s role. So we did not fight for the leadership of the union for ourselves alone, for our own advancement and aggrandizement. The New Caucus has never been for itself alone, but to realize the right to education of the children of the people, the children of the whole people.